Floyd Cooper

January 8, 1956 – July 15, 2021

Early Life

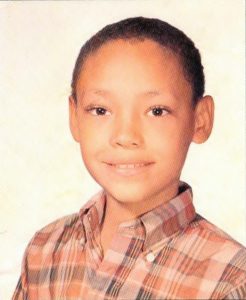

Floyd, the son of Ramona (Williams) Cooper, a beautician, and Floyd Cooper Sr., a house builder, was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma on January 8, 1956.

As a three-year-old, Floyd watched as his father worked on a house in Bixby, Oklahoma. “He built the house we lived in on a tract of land granted to the family of my Muskogee Creek Indian grandpa in part of that whole Native tribe relocation program famously known as The Trail of Tears.”

“I plucked a piece of gypsum board from a scrap heap left by my dad who was perched on a ladder, working on building our house. I used that chalky piece of wallboard to scratch little shapes onto the side of Dad’s house.”

Furious at Floyd’s act of destruction, his father made him erase every bit of the drawings he had done. The act of scrubbing away what he did was the beginning of Floyd’s signature art style, a method of subtracting color to produce an image. He said that he had “been erasing ever since.”

After his parents divorced, Floyd moved often, finding himself living in housing projects and attending all 11 of the elementary schools in North Tulsa. “With each new school, I quickly learned the currency of my art. I would seek out the art teacher and ‘buy’ myself a new friend with my artwork.” His teachers recognized his tremendous talent and continued to encourage him all the way through high school. He was awarded a scholarship to the University of Oklahoma to continue his art education, then graduated with a BFA in 1978.

Career and Technique

Floyd began work in advertising, and landed a job at Hallmark Cards in Kansas City, MO. Among his duties was changing old greeting cards by erasing the art. It helped him to further develop his signature technique, a subtractive process he dubbed “oil erasure” for which he washed a board in oil pigment, and then used an eraser. “It’s basically erasing shapes from a background of paint,” he once said. He also described that he enjoyed the soft lines that the eraser created, and that he didn’t enjoy making sketches before beginning a project. However, sometimes he used an orange color pencil to help guide where he was working.

He often used real models for the characters in his books, relying on his sons and their friends (who he once joked did not come cheap!) or other family members. He believed that “real faces = real art. That’s the goal, anyway.”

In 1984, he moved to New York City, hoping to pursue a career doing his own illustrations. He secured his first agent, Libby Ford, who got his portfolio seen at various children’s book publishers. He did some book jacket work, but his first picture book assignment was for Eloise Greenfield’s GRANDPA’S FACE. That job was quickly followed by Margaret Davidson’s THE STORY OF JACKIE ROBINSON, BRAVEST MAN IN BASEBALL. Both were published in 1988 by Philomel Books.

From that moment, Floyd never stopped working, amassing an impressive catalog of over 100 books, some of which he also wrote. Patricia Lee Gauch, his said the project with Greenfield “was a door opener for Floyd as an artist, but it led to his personal discovery that he could write as well as create art. As author and artist, then, he chose stories that honored and celebrated the individual.”

In 1994, 6 years after his first illustrated picture book, Floyd came out with a solo project. He wrote and illustrated COMING HOME: FROM THE LIFE OF LANGSTON HUGHES, also published by Philomel. He went on to write 7 more books, including a 1966 novel titled THE OLD WOMAN WHO LIVED TOO LONG. But he didn’t primarily see himself as a writer. “I will always be an artist first. I see my writing as an extension of my illustrating. The approach to ‘building’ a story with words and phrases is no different than ‘building’ a painting with brushes and pigments.” He continued, “In my journey to becoming an artist who writes, I tend to start my idea process with simple, concrete messages that relate to what kids may be experiencing as they navigate through childhood and adolescence putting together building blocks of the foundations on which they will become adults.”

Accolades

In 1994, along with the publication of his solo project, he won the first of many awards. The Coretta Scott King committee awarded him an honor for his illustrations in BROWN HONEY IN BROOMWHEAT TEA by Joyce Carol Thomas.

In 1995, he was also awarded the Coretta Scott King honor for MEET DANITRA BROWN by Nikki Grimes.

In 1999, he would receive another Coretta Scott King honor with Thomas for I HAVE HEARD OF A LAND. Years later, Floyd would say there was something magic about his work with Thomas, because every time they worked together, the book would be awarded in some way. Their biggest win came 10 years later in 2009, when Thomas’s THE BLACKER THE BERRY garnered him the Coretta Scott King Illustrator award—the top prize. The book also won an author honor for Thomas, while Floyd racked up a second honor for the illustrations on BECOMING BILLIE HOLIDAY by Carole Boston Weatherford. It was a banner year. And there was more to come.

Another of Floyd’s solo projects, MAX AND THE TAG-ALONG MOON was named Highly Commended for the 2014 Charlotte Zolotow Award and was a nominee for the 2015 Keystone to Reading Book Award. He described MAX as his favorite book “because Dolly Parton added it to her Imagination Library…and it has sold over 1.5 million copies.” Also in 2015, the Society for Children’s Book Authors and Illustrators granted Floyd a Golden Kite Award for his illustrations in Kristy Dempsey’s A DANCE LIKE STARLIGHT.

In the 2000s and 2010s, Floyd’s books continued to rack up accolade after accolade. But Floyd’s most personal project and the one that would receive the greatest praise was yet to come.

Very Personal Project

When Carole Boston Weatherford decided to take on the Tulsa Race Massacre, a little-known but crucial moment in American history, Floyd was the only person she wanted to illustrate the book. In fact, she approached him before she even sold the manuscript. Usually, the illustrator does not become involved in a project until after a publisher is involved. “Because of Floyd’s roots, I knew he would bring passion to the difficult subject. Together, we strove to give voice to the victims and the survivors whose stories were never told and whose losses may never be fully measured.”

Floyd’s grandfather, C.D. Williams had told Floyd and his cousins stories about “Black Wall Street” and Greenwood Avenue in Tulsa, Oklahoma when they were young. The vibrant Black community had been Williams’ home, and when the massacre happened, his grandfather “was there, a live witness to it all.” From the strength of his grandfather’s storytelling, the images of the burning of this historic Black neighborhood and the people who had to flee to safety played like movies in Floyd’s mind. He drew on that for Weatherford’s book and dove deeply into the work, drawing for months.

When UNSPEAKABLE: THE TULSA RACE MASSACRE was published in February 2021, it was to roaring praise. Many felt it was Floyd’s best work yet. The delicacy that he brought to such a violent moment in history made it accessible to young readers without losing any of the gravity of what occurred.

In January, just before the book was published, Floyd addressed readers, sitting in a room with the lights of a Christmas tree casting a soft glow next to him. “I’m really glad to speak with you this evening,” he said. “There’s something I want to tell you. It’s something that’s been on my chest for a long time. And I’ve got to get it out. I have long wanted to tell or draw some of the stories my grandpa would tell us kids on warm summer Muskogee evenings, sitting on the front porch under the heady smell of the grain silos.” Weatherford, he said, had somehow captured exactly his grandfather’s story the way he heard it when he was a child. The camera angle changed to an overhead shot of the book and his hands turning the pages as he read.

Later that year, and the next, the book would bring Floyd the most honors he had ever had for a single project. UNSPEAKABLE was named an honor book for The Caldecott Medal, the biggest award for illustration in the children’s book industry. It won the Coretta Scott King Award for both illustration and text. It was a Sibert Medal Honor, an award given for informational books, and it was longlisted for the National Book Award.

Floyd did not see any of it happen. He died of cancer on July 15th, 2021, just a few months after sharing the beautiful remembrance of his grandfather and reading from the book.

It was not his last publication, however. At the time of his death, he was working on a follow up to 2017s WHERE’S RODNEY, with a picture book called TASHA’S VOICE. It would be published in 2024 after a mentee of Floyd’s, Daria Peoples, finalized the illustrations he began.

Legacy

The news of Floyd’s death hit the children’s book community hard and fast. People remembered him as cool, a gentle soul, kind, always friendly, and immensely generous. The tributes and well-wishes poured in to his social media accounts, and on blogs like The Lerner Blog, the publisher for UNSPEAKABLE, as well as The Brown Bookshelf, a platform that celebrates kidlit creators of the African diaspora. Readers who never met him, but who had enjoyed his books over the years offered their remembrances in the comments, revealing that his reach was wide and deep.

Over the years, Floyd was generous with his time for fellow kidlit creators, whether they were illustrators or writers. He mentored many artists, and gave classes at various conventions around the country and at the Highlights Foundation in Milanville, PA. Highlights set up a scholarship and cabin in his honor in 2019. The scholarship benefits indigenous artists and artists of color. The cabin is filled with several of his art pieces and many of his books. It is a legacy to his obvious passion for sharing his art, which was most evident in his presentations for kids. During school visits, after demonstrating his subtractive technique, he would often give out erasers so students could try out his method themselves.

Career Overview

In his 37-year career in children’s publishing, Floyd illustrated book covers, and over 100 picture books of which he wrote 7. He also wrote one novel.

His accolades include 3 Coretta Scott King Honors, 10 ALA Notables, 3 NAACP Image Award nominations, a Jane Addams Peace Award Honor, numerous Bank Street College Book of the Year Honors, Parent’s Choice Honors and starred reviews from Booklist, Kirkus, and School Library Journal, the Texas Bluebonnet Award short list in 2011, the Grand Canyon Reader Award short list, the Georgia Book Award short list, nominated for the Keystone to Reading Book Award in 2015, was longlisted for the National Book Award in 2021, and received a Caldecott honor in 2022.

His top awards were the Coretta Scott King Award in 2009, the NJ Center for the Book Inaugural Award, the Simon Wiesenthal Gold Medal in 2011, an IPPY Gold Medal in 2011, the Pennsylvania School Librarians Outstanding Illustrator in 2011, the Sankae Award of Japan in 2012, the Arkansas Diamond Primary Book Award in 2012-2013, the Charlotte Zolotow Award in 2014, the SCBWI Crystal Kite Award in 2015, and a second Coretta Scott King Award in 2022.